‘Cathedral du Nord’

I went to St. Mary Star of the Sea Church in Newport thinking I was going to see something of local interest. What I found was a church that might be the only one if its kind on the planet.

The church sits on a hill southwest of downtown Newport, facing north over Lake Memphremagog, its granite like that of Owl’s Head Mountain just over the border in Quebec. An old mountain and a newer one, both made of the same lava that emerged from the Earth about 300 million years ago.

French Canadians once called St. Mary’s “Cathedral du Nord,” Cathedral of the North. They laid the cornerstone in 1904 and worked for five years, hauling the massive granite blocks by teams of horses and oxen from three quarries. The closest was two miles away across the bay on Pine Hill. Quarry Road, where they cut the detailed pieces, is five miles away.

Inside, you might first notice unique murals that cover the walls. Montreal artist N.O. Rochon copied the images from French originals, such as the Presentation of Mary. She’s at the temple gate with hands clasped, embraced by her mother, Anne, as the priest receives her in front of pillars like the ones at the front of St. Mary’s.

Very much Vermont’s Michelangelo, Rochon lived in the choir loft while he painted, where one panel is still blank, as he died before finishing.

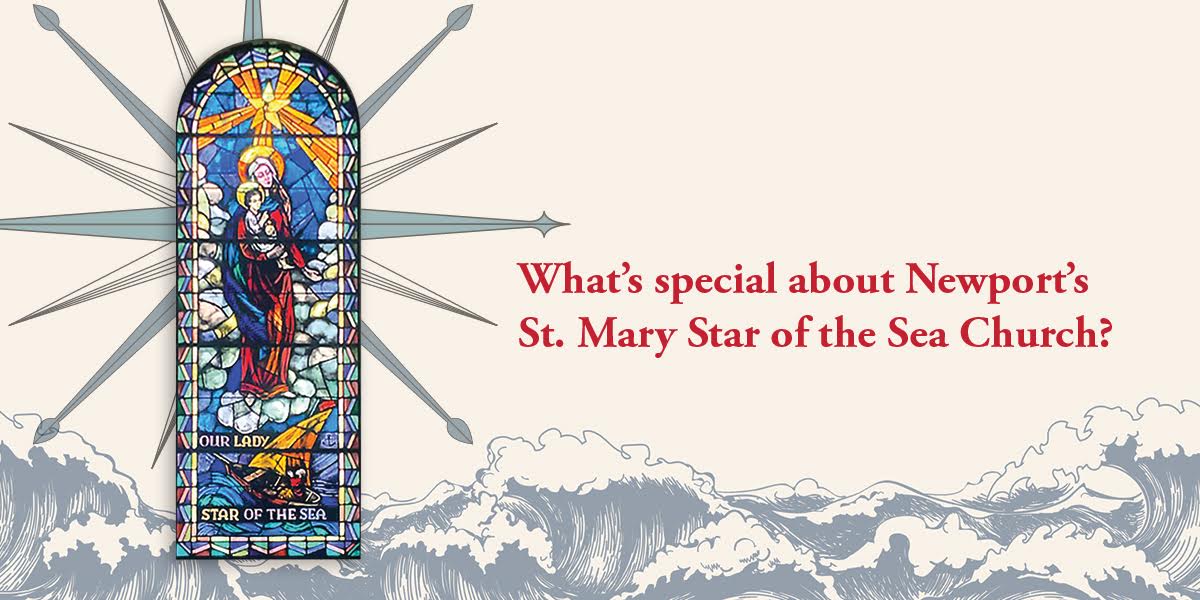

Jumping out from the murals is the striking color of 12 large stained-glass windows installed in the 1940s. A pastor, from a wealthy local family, thought the originals were “underkill,” and paid for the windows himself.

Most of the windows depict apparitions of Mary, such as Lourdes, Fatima and Guadalupe. There is one for Maris Stella, Latin for Mary Star of the Sea, guiding a ship through a storm. Churches to Maris Stella are often built at seaports as she is the patroness of seafarers.

“Ave Maris Stella” is one of the oldest Latin hymns, going back to as early as the 8th century.

Sailors sang the hymn at sunset for a safe night’s passage. The North Star, the most important for navigating before computers, was Mary’s star, the direction that the church faces.

The Barker family of seven, parishioners at St. Mary’s, are making Ave Maris Stella a part of their prayer life. They sing it together every morning and every night.

“Ave Maris Stella is beautiful prayer for so many reasons and an important hymn for everyone,” the father, Jonathan, said, “But especially for our church, where the silver statue of Mary looks over the lake and is lit up at night. The kids connect with her, and you hear it in the earnestness of their voices when they sing and when they talk about the song.”

“It’s a warm, nice gaze from Mary,” Rafe, 6, explained. “And it also sort of connects to Jesus. The nice thing about it is the song is helping you.” Aminata, 8, agrees. “When you sing it, you feel close to Mary.”

When I suggested this was a new kind of catechesis, one that integrates ancient tradition, local parish history, church architecture, the land and deep devotion, Barker agreed.

“To that I would add a cosmic dimension. There’s nothing bigger than the stars, and the song brings them to the kids and ties it all together through Mary’s loving presence. There so many storms in life, and it makes real that Mary is there guiding us through them.”

This new catechetical approach — cosmic vision embodied in local practice — was uniquely captured by the best story I heard during my visit to St. Mary Star of the Sea. During the construction, an ox, upon finishing the long walk from one of the quarries and delivering the stone, collapsed at about where the front stairs are. Unable to move it, the laborers buried it there.

The ox and its horns were an essential part of the temple in Jerusalem. The temple had two horned altars, one for the sacrifice of incense and the other for the sacrifice of oxen and rams.

Pope Benedict XVI reminded us in “The Spirit of the Liturgy” that along with the synagogue, all Catholic churches draw from the imagery and traditions of the temple. Montreal artist Rochon knew this, as he painted Jerusalem behind the altar, the view from the temple.

In the Old Testament, horns and ox imagery are also important images of messianic power [i.e.] and fulfilled by Christ, called by Zacharias “a horn of salvation for us in the House of David” (Lk 1:69) and John a seven horned lamb (Rv 5:6).

If the ox story is true — and I think that it is — the church itself contains within it a sacrifice of the old temple, an ox that gave its life to build the church. St. Mary Star of the Sea, in other words, stakes a greater claim to our temple ancestor than maybe any other church in the world.

And with the children now singing it, St. Mary Star of the Sea seems poised to become the Cathedral of the North that old-timers saw.

— Damian Costello is the director of postgraduate studies at NAIITS: An Indigenous Learning Community, a speaker with the Vermont Humanities Council and a member of St. Augustine Parish in Montpelier.

—Originally published in the Spring 2023 issue of Vermont Catholic magazine.