‘Reading the bible in stained glass’ at St. Augustine Church

Church windows are sometimes called “the bible in stained glass.” At St. Augustine Parish in Montpelier, we’ve begun to read them again.

The stained-glass windows are the most prominent feature of St. Augustine’s, but we’ve only now begun to appreciate their artistic and historical value. Wilbur Herbert Burnham, a key figure in the revitalization of the art of stained-glass in the early 20th century, installed the windows in 1938.

Burnham’s windows are found in prominent churches such as the National Cathedral; they were featured in the April 3, 1939, issue of Life in “Stained glass has U.S. Renaissance: Gothic craft restored after 500 years.” His work is so important that the archives of his studio are kept at Archives of American Art, a Smithsonian Institution.

More importantly, at St. Augustine’s we’re beginning to open ourselves up to the way the windows help draw us into the mysteries of our faith.

Blue — the first and most powerful impression the windows make before even looking at them — is intentional. The color blue represents the sky and the heavenly realm. Etched into the blue background are plants and flowers, representing Eden and the New Heaven and New Earth, our origin and destination.

When you look at the windows directly, the faces of the angels and the Communion of Saints emerge. This great cloud of witnesses, like in the Book of Daniel, shine “like the stars forever” (Dan 12:3). The artform itself teaches that light not only acts on it but through it. The windows enact the living character of the saints who “shine and dart about as sparks” (Wis 3:7) as they intercede for us.

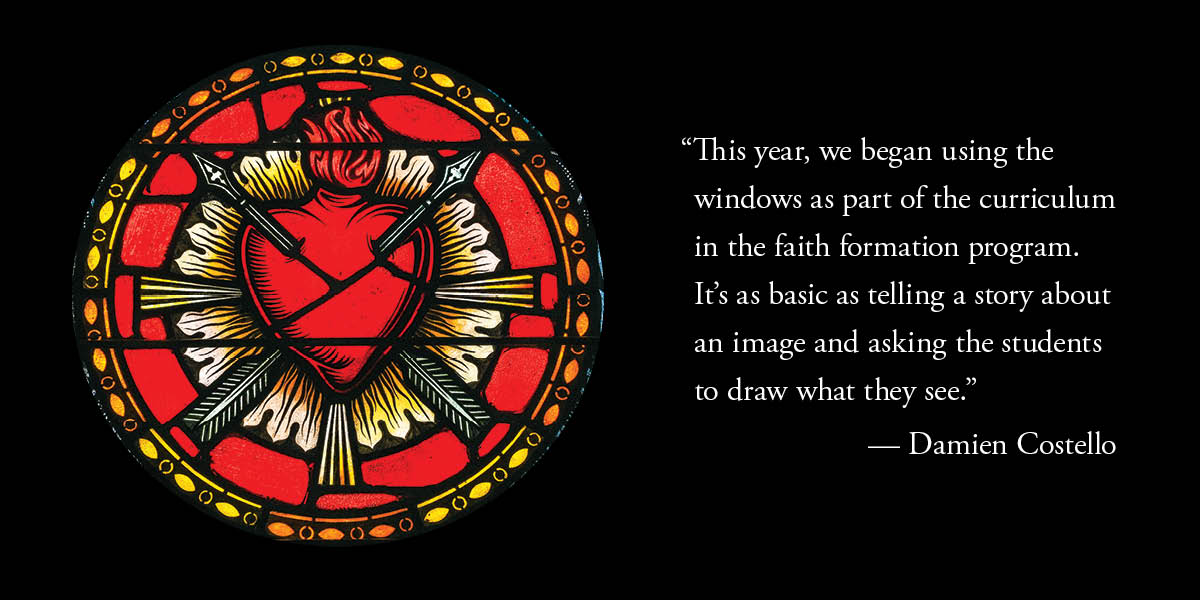

Burnham included extensive symbolism in St. Augustine’s windows. A beehive honors “Mother Bee” and her gift of fragrant wax for candles that is proclaimed during the Easter Vigil in the Exsultet. A pierced heart evokes both the Sacred Heart and with its placement below St. Augustine his idea of the restless heart.

While seemingly multiple separate windows filled with diverse images, there is an overall unity to their design. Like the pages of a book they tell the story of Christ. Starting in the eastern corner with the Annunciation, 28 panels — four each on seven windows — portray the entire life of Jesus.

St. Augustine’s stained-glass windows are not only a single piece of art, but one that dynamically engages the faithful. Every day, the sun re-tells the story, “circling” the windows and progressing through Jesus’ life. In summer, the sun sets at about the window with the panels portraying His death and entombment and rises the next morning where the tabernacle sits.

This year, we began using the windows as part of the curriculum in the faith formation program. It’s as basic as telling a story about an image and asking the students to draw what they see. My daughter drew the Sacred Heart/Mother and Child, and I know from talking to her that the meaning stayed with her.

I was surprised that the bigger ideas stick as well. Our second class was a scavenger hunt designed to introduce the children to the images on the stained-glass windows and their deeper meaning. A month later, a third grader surprised me in class. “The sun tells the whole story of Jesus,” she told me unprompted, and then explained how.

This shouldn’t have surprised me as art, whether stained-glass windows or stations of the cross, is a pragmatic catechetical tool that helps enact what it represents.

Beautiful art, St. John Paul II wrote in his 1999 “Letter to Artists,” mirrors the incarnation and doesn’t merely communicate information but serves as windows into mystery. Art holds us together: “Beauty, like truth, brings joy to the human heart and is that precious fruit which resists the erosion of time, which unites generations.” Churches reveal through their art the “soul of a people.”

St. Augustine Church, like all Catholic churches, is not just an empty shell where the sacraments occur. This holy, consecrated ground is a thick tapestry of meaning and mysteries, a web of connections to our ancestors in faith, both universal and local.

By engaging our children with the art of our church, we hope St. Augustine’s becomes one of their homes, a beautiful window, in the words of St. John Paul II, “to that infinite ocean of beauty where wonder becomes awe, exhilaration, unspeakable joy.”

— Damian Costello is the director of postgraduate studies at NAIITS: An Indigenous Learning Community, a speaker with the Vermont Humanities Council and a member of St. Augustine Parish.

—Originally published in the Winter 2022 issue of Vermont Catholic magazine.