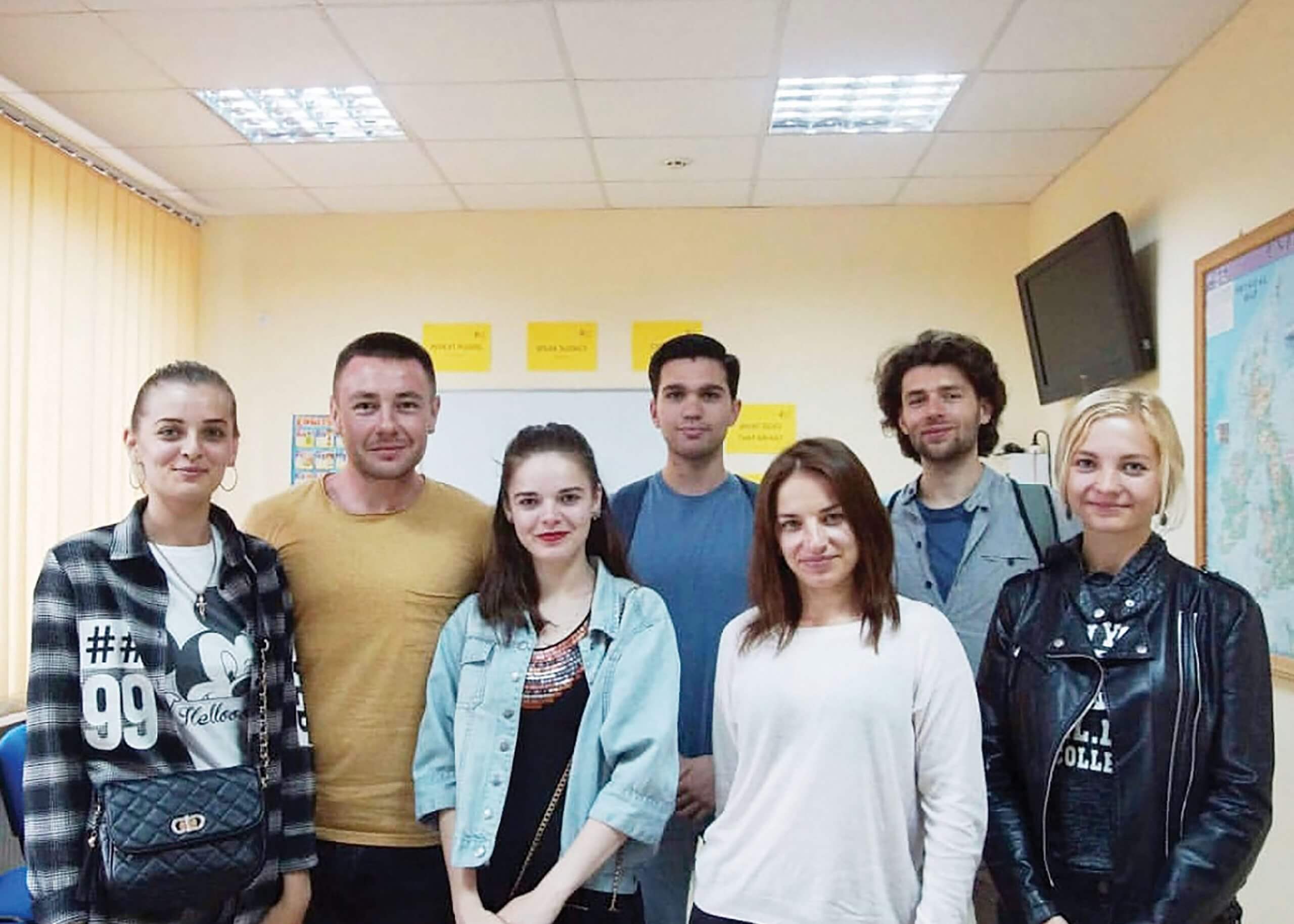

Stephen Coutcher, a Rhode Island seminarian who spent the summer of 2018 teaching English in Ukraine, urged those who feel helpless about the current situation there to pray for peace.

The 23-year-old, in his second year of studies at Our Lady of Providence Seminary in the Diocese of Providence, said he feels a closeness to the country and struggles with what is taking place there now.

Coutcher, who studied contemporary Russian politics, language, culture, literature and the Cold War, said the current Ukrainian crisis is neither simple nor something completely out of the blue.

“I know that the Ukrainian people, as a whole, do not entirely present a united front against Russia, as the media may portray them. … There is a vast divide within the country between Russian government sympathizers and Ukrainian nationalists, and everybody in between,” he explained.

Pro-Russian nationalists largely reside in Eastern Ukraine, which shares its border with Russia, and Ukrainian nationalists largely reside in the western part of the country, closer to the shared border with Poland.

In meeting people of both sides of the issue during his time there, Coutcher quickly learned that there was little to no common ground between the two extremes.

“This polarization goes far deeper than the current political divide in the U.S.,” he told the Rhode Island Catholic, Providence’s diocesan newspaper. “It is incredibly hard to conceive of any type of resolution to the conflict with those who want to join Russia, those others who want to remain a sovereign nation, vehemently opposed to Russia, and those in the middle.

“Especially geographically speaking, one could never conceivably divide up the country in such a way in which everybody would get what they want.”

Four years ago, Coutcher spent his summer in the industrial town of Khmelnitsky, teaching mostly in Russian for beginner students and in English for his more advanced classes. He explained that Ukrainians are generally fluent in both Ukrainian and Russian and because Khmelnitsky lacked tourism, people only spoke either Ukrainian or Russian on the street, in shops and in restaurants.

“That was great for me because I purposely went there to try to further develop my Russian. However, the language gap mirrors the overall cultural divide between the two nations,” he said. “Those cities in Western Ukraine choose to speak strictly Ukrainian, while those in the East speak almost exclusively Russian.”

He found this out the hard way during a visit to Lviv, a major city in Western Ukraine.

At a restaurant, he asked, in Russian, for a table and the hostess asked him, in Ukrainian, if he spoke English. He said he did, but that he didn’t speak Ukrainian. She told him: “We do not speak Russian here; we will speak English or Ukrainian!”

“I learned my lesson pretty quickly,” Coutcher said. “Somewhat ironically, when I visited Kyiv, the capital city, I found that pretty much everybody there chose to speak Russian.”

He said the Ukrainian people he met were extremely hard-working, dedicated and loyal.

“They would do anything for you, especially if you found yourself in need of something. They made sure I had everything I needed, and that I was well taken care of,” which he said goes against how some inaccurately describe their coldness.

Coutcher said it is “imperative that the conflict be resolved as soon as possible and in the best way possible,” which he acknowledged is “probably not going to make anybody happy.”

“Both sides are probably going to have to give in some ways, unless Western Europe suddenly rises to the occasion and defends Ukraine beyond sanctioning Russia,” he added.

The seminarian said prayer and fasting are powerful tools for those who feel helpless watching and reading news reports of what is happening.

“With the season of Lent underway, I would encourage all to take a day to fast and pray specifically for peace in Ukraine. I would encourage them to do it on a day it is already not obligated by the church,” like Good Friday, he added.

“If that is too much, maybe say a rosary, asking for our Blessed Mother’s intercession, specifically for that intention. We are certainly not helpless when we are harnessed with the power of prayer,” he said.

—Laura Kilgus